Abstract

In this article, we intend to present the connections between Educommunication and the Actor-Network Theory (ANT) that make it possible to reflect on the possibilities of creating learning networks via ubiquitous media. In this way, this search expands the conceptions of digital social networks and how they can overcome the patterns of connections which are expressed in cyberspace, opening up fields of discussion in the educational process.

Thus, some concepts are analyzed, such as the Actor-Network Theory (Latour, 2012), Social Networks (Recuero, 2014) and Ubiquitous Networks (Schöninger, 2017), aiming to present a kaleidoscope, that is, as a lens that allows us new perspectives for the investigation of the social network and its developments in digital culture.

It is important to problematize the context of integration of ubiquitous media in pedagogical mediation and verify how ubiquitous media can contribute to the construction of learning networks. The methodology selected for this study was of a theoretical-reflective nature and this research allowed us to show a network as an Actor-Network report in which it is possible to develop some important actions in which each actor can be recognized as an active mediator, which causes changes and not only observes what happens in their context.

Keywords: education, educommunication, ubiquitous media, Actor-Network Theory

En este artículo, nosotros pretendemos presentar las conexiones entre la Educomunicación y la Teoría del Actor-Red (TAR), conexiones estas que nos permiten reflexionar sobre las posibilidades de crear redes de aprendizaje a través de medios ubicuos. De esta forma, esta búsqueda amplía las concepciones de las redes sociales digitales y cómo estas pueden superar los padrones de conexión que se expresan en el ciberespacio, abriendo campos de discusión en el proceso educativo.

Por lo tanto, em este artículo se analizan algunos conceptos, como la Teoría del Actor-Red (Latour, 2012), Redes Sociales (Recuero, 2014) y Redes Ubicuas (Schöninger, 2017), con el objetivo de presentar un caleidoscopio, es decir, como un lente que permite a nosotros observar nuevas perspectivas para la investigación de la red social y sus desarrollos en la cultura digital. Se vuelve importante problematizar el contexto de integración de los medios ubicuos en la mediación pedagógica y verificar cómo los medios ubicuos pueden contribuir a la construcción de redes de aprendizaje.

La metodología que fue seleccionada para este estudio es de carácter teórico-reflexivo y esta investigación permitió mostrar una red como un informe Actor-Red en el que es posible desarrollar algunas acciones importantes en las que cada actor puede ser reconocido como un mediador activo, que provoca cambios y no sólo alguien que observa lo que sucede en su contexto.

Palabras clave: Prospección tecnológica, energías renovables, celdas solares, impacto.

Introduction

In this article, we intend to broaden the understanding of digital social networks to overcome the patterns of connections expressed in cyberspace, through ubiquitous media and, thus, bring them to the context of contemporary educational processes, having the school as an object of analysis as a hybrid space, in which such immersive media and technologies are created. In this way, we understand that such route is elaborated around a central question to understand how these networks are modifying the informational and communicational processes of/in society, as well as influencing new formative and educational processes. In this way, the study of social networks on the internet is concerned with understanding how social structures arise, what type they are, how they are composed by communication mediated by non-humans and how these are capable of generating informational flows and social exchanges (Recuero, 2014). And it is from this perspective that it will be possible to envision that such conceptions encompass new pedagogical possibilities with ubiquitous media (Schöninger, 2017).

That said, it can be considered that such conceptions and initial reflections are important elements for our analysis proposal, understanding that some conceptions are not easily understood regarding the objects discussed in this essay, which merge and have direct repercussions on society, on the actors and at school - as a social space. Therefore, what would the word “social” mean in this context? Who are the social actors that make up such contexts? And how to consider the connections between such actors? What types of dynamics can influence these social networks? These will be questions which will be the fabric of this article.

First, we emphasize that we resorted to the Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to support some of the discussions, such as kaleidoscopic lens which will allow us other perspectives for the investigation of the social network and its enthusiasms in digital culture, as well as Santaella and Lemos (2010) understand that ANT helps us to avoid the functionalism that is in many media studies, as it also insists on the hybridization of what is called social relations. However, this study does not have as its main objective just to achieve a pedagogical functionality for ubiquitous media (Schöninger, 2017), considering transforming them into previously formatted virtual learning environments. In fact, this article had a theoretical-reflexive concern in developing Christian emotions with the connections, associations, translations, and transformations between the diverse actors that form the social networks in these school spaces, that is, through the constitution of new processes educational, with or without any school pretensions, there are appropriations of digital culture (voluntarily or involuntarily).

It is also relevant to say that these studies have been taking place in Brazil, contextualizing that until the 1990s, personal computers were practically inaccessible to a large part of the Brazilian population. From 1995 onwards, the use of computers and the internet became a more intensive part of people’s daily lives.

The Actor-Network Theory (ANT)

EAs the Actor-Network Theory (ANT) is one of the main theoretical foundations of the thesis, it becomes extremely important to reframe its meanings for the study. In this way, we seek the origin of the theory to support and enable a possible link to Educommunication and this research. We begin, then, by highlighting that ANT originates from studies of science, technology, and society. It applies, mainly, in cases where non-humans may have roles as actors (intermediaries or mediators) in social relations and “not mere lived projections” (Latour, 2012).

Thus, it is worth emphasizing the difference between intermediary and mediator. An intermediary is an actor who conveys meaning or force without transforming it: defining what goes in already defines what goes out. What enters the mediators never exactly defines what comes out, as their specificities must always be considered. Mediators still transform, translate, distort, and modify the meaning or elements they supposedly convey. For us to understand these social relationships between mediators and intermediaries, we need to better understand ANT and its concepts.

Latour (2012) points the origin of this approach was the need for a new social theory adjusted to science and technology studies, quoting Callon and Latour himself. However, Latour (2012) mentions it started with three documents: Latour, 1988, Callon, 1986, and Law, 1986. It was at this time that non-humans – microbes, oysters, stones, and sheep – presented social theory in a new way. (Latour, 2012). The author explains that the expression “non-humans”, like others chosen by ANT, has no meaning.

With this, Latour intends to affirm that the action is a role assumed in a collective that is associated and that the actor is not the source of an act, but the moving target of a broad set of entities that swarm in his direction (Latour, 2012). And as he does in a good part of his book “Reaggregating the social”, Latour (2012, p.109) uses good humor to state that the expression non-humans does not refer to goblins in red hats acting at atomic levels, but rather to elements that are part of our daily routine, smartphones, for example, and that ANT is part of the collective and belongs to the social, just like humans.

In this way, Latour (2012) also proposes that from now on the word “society” will be replaced by the word “collective” and explains that when we perform a collective action, we will unite several different forces, and this will guarantee freedom in movement, with continuities and discontinuities of modes of action, depending on network arrangements. In turn, the hyphen in the expression “Theory-Actor-Network” precisely represents this connection between subject and object through the network.

It is also, according to Lemos (2013), a matter of time, since “actor-hyphen-network” points to circulation, to what “does-to-do” and not to the immobility of one of the poles of action. That is, the hyphen reveals the importance of the mobility that is essential for both parts: the first part (the actor) reveals the dwindling space in which all the great ingredients of the world begin to be incubated; the second (the network) explains by what vehicles, traces, trails and types of information the world is placed inside these places and then, once transformed there, expelled from within their narrow walls.

This is the reason why the hyphenated “network” is not there as a surreptitious presence in the context, but rather as what connects the actors (Latour, 2012).

Mobility is in this movement of making others do something and that is why ANT, in the words of Lemos (2013), moves away from everything that is fixed: essences, structures, unifying systems. Thus, Latour (2012), who became the best-known author of ANT, takes on the task of “unfolding the social” and, for that, he proposes that we replace the place of nature and things, as well as humans and their artifacts, undoing the modern division between nature and culture, or even between subject and object. With this, the author wants us to understand that all the work of science happens through the medium, that is, it is a work that transits between both: nature and society.

By studying Latour’s works more deeply, it is possible to conclude that this given nature and the society to be transformed are effects of a set of practices and mediations, rather than distant and opposite causes. In this sense, our essay is precisely to accompany the process by which the social has been assembled and disassembled, both by nature itself and in human society. It is also in this sense that, in his work “Jamais fomos modernos” – which can be translated to “we have never been modern” – the author draws attention to the fact that the modern men were not mistaken in wanting objective nonhumans and free societies. Only their certainty that this production required the absolute distinction and continuous repression of the work of mediation was wrong (Latour, 1994).

Therefore, the question is not to separate knowledge about nature from men, but to follow the network that unites humans and non-humans and that allows the construction of our collective. And these networks, which are not only made up of discourses, sounds, images, or languages, which are at the same time real like nature, narrated like discourse and collective like society (Latour, 1994).

In this context, Latour (1994) points out three characteristics of ANT: non-humans cannot only support symbolic projections, but actants; the social cannot be the most variable constant; any deconstruction must anticipate how to reassemble the social again. In summary, in the words of Lemos and Pastor (2016), the social is not a thing, it is the whole association, it is the result to be always renewed, from associations between humans and non-humans, and not what only structures the associations between subjects.

Lemos (2013), in the book “a Comunicação das coisas” – which can be translated to “the Communication of things” – explains that the actant is the mediator, the articulator who will make the connection and set up the network within himself and outside himself in association with others. He is the one who “makes do”. And the actant is both the ruler, the scientist, the laboratory, the chemical substance, the graphs, the tables... that is, humans and non-humans on the same terrain, without hierarchies previously defined.

These actants are, therefore, the mediators that promote network actions and associations; intermediaries, on the other hand, are human and non-human elements that only transmit and/or reproduce existing actions and associations, without, however, modifying them. There is no separation between humans and non-humans, but a hybridization in which new actants are formed by association with new objects or new actors. Let’s see examples of these actants acting in our daily lives: anyone who is in doubt about how to install a program on his/her computer can watch a video on YouTube with the step-by-step and solve the case by himself/herself. However, when we are at home studying, writing a thesis, for example, and thousands of questions arise and academic peers are in other cities, or even in other countries, a WhatsApp call can overcome the geographical distance and connect the pairs to discuss theories, talk about everyday life or even vent about the anguish experienced by a human with their peers. It is noted that a detour in studies was necessary so that new translations could be composed, and the essay concretized by rethinking new translations or, according to Latour (2016) at the same time transcribing, transposing, displacing, transferring and, therefore, transporting transforming.

With the example above, by joining WhatsApp we are no longer isolated from our peers by a geographic obstacle and shift the initial interest from discussing doubts to talking about everything. That means, this ubiquitous media, in addition to transforming the ability to communicate between distant people, also shifted the initial objective of the story and originated the actant “I + WhatsApp” – which mediated the dialogue and was both an actor and the network.

From the approach proposed by TAR, we understand that WhatsApp ends up playing an active role in the narrative, manifesting itself as a mixture of subject and object, since it provides a direct interaction with new communicative properties, which would not have been possible if we had accessed just a video, for example. Faced with a web of meanings, dialogues, and languages, we can affirm the importance of considering the proliferation of hybrids in different situations, especially in educational spaces. As seen in the narrative, “things” are not isolated, they are “caused” at all times, within specific situations (Oliveira & Porto, 2016).

Oliveira and Porto (2016) discuss ANT and Education based on the heterogeneous flows and hybrid connections that emerge in the school space. In this context, they state that it is necessary to understand that the configuration of the school and the learning environments are always hybrids. They are naturally formed by the association between individuals and technologies/objects, that is, since their origin and, mainly, today with digital technologies and infocommunication objects, and not by the hierarchical separation of these into subject who owns the action and the inert and passive object, in all situations.

With this understanding, the school is a hybrid space, that is, formed by teachers, students, managers, classrooms, laboratories, computerized rooms, media, regiments, and many other human and non-human actors, after all, there is no way to separate humans and non-humans, on the contrary, we must associate them so that they produce multiple mediations - networks in search of new knowledge. Meanwhile, the computerized rooms and the ubiquitous media are nothing in themselves without the associations and action plans (planning) of the various mediators (teachers from the Computerized Room – CR – and from the different areas) at each new association.

In other words, ANT can offer a differentiated perspective to the construction of a thought about these associations between the different actors, mediators, or intermediaries, who are part of the school routine and the networks that are formed from the circulation of the action between them. Under that prism, looking at networks is more interesting than looking at structures that will say nothing about the association in play. This position is a way of revealing the unfolding of mediations and the constitution of actants, their negotiations and future stabilization. It is therefore interesting to see the circulation between one thing and another (Lemos, 2013).

As it was perceived, when drawing attention to associations, in exchanges that take place in the school space, it becomes noticeable that such actors can detach themselves from established, crystallized structures and open themselves up to new experiences made possible by new associations. However, instead of prohibiting the use of cell phones in the classroom, for example, on the grounds that the school structure does not allow it, we can start a pedagogical work aimed at another movement, that of reflection on what associations would be possible when using this non-human in the school space.

Adding to the discussion, Latour (2005) states that no knowledge travels without scientists, laboratories, and fragile chains of references. And this is how the network is understood, as space and time in motion, that is, it is not where things pass, but what is formed in relationships and with things. Understanding how these digital social networks form helps us to understand by what vehicles, what layouts, what trails, what kinds of information is the world being brought into these places and, after being transformed there, is being pumped back out of their narrow walls (Latour, 2005).

In this texture, the author proposes a mapping that makes it possible to look at all the connections and transformations in each set of actions or practices, established in the networks that are formed in the relationships (mediations or translations) around the construction of so-called scientific knowledge. Thus, it is possible to produce different ways of looking at the social and the network that builds and remakes it permanently.

Therefore, to broaden this view, the elements that are part of digital social networks will be discussed further on, bearing in mind the articulations with social media and ubiquitous media for a careful understanding of the dynamics of these networks.

Digital social networks and ubiquitous media

A network is a metaphor for observing the connection patterns of a social group, based on the connections established between the various actors. The network approach focuses on the social structure, where it is not possible to isolate social actors or their connections (Recuero, 2014).

The expression “social networks” has been used since the mid-twentieth century to refer to norms and dynamics of social interaction. Nowadays, this expression is usually used to refer to “online platforms”, such as Facebook, Tuenti, Instagram, among others (Aparici, 2012). As previously mentioned, in this study we understand that these online platforms can be defined as ubiquitous media and digital social networks as the connections, links and exchanges that we establish in these environments.

These media, says Schöninger (2017), in addition to expanding the connection capacity among people, also allow many networks to be created in these spaces for different purposes. We use the ubiquitous media to arrange a meeting with a friend, an appointment at the dentist, discuss politics in its various scopes, in short, routine activities, from simple to complex, are articulated by these media. The author quotes Sá Martino, 2014, stating the media are there, exchanging an almost infinite amount of data at all times, and in general, it is only when they fail that we perceive them again (Schöninger, 2017).

We agree with Recuero (2014) when the author states that the internet has brought many changes to society, and the most significant for this research is the possibility of expression and socialization through communication tools mediated, initially, by computers and, currently, also, by smartphones and tablets. In this context, when we interact and communicate, we leave traces that allow the recognition and visualization of our social networks, since, according to the author, it is the emergence of this possibility of studying interactions and conversations through the traces left on the Internet that gives new impetus to the perspective of studying social networks, from the 1990s onwards. It is in this context that the network as a structural metaphor for understanding groups expressed on the Internet is used through the perspective of social network (Recuero, 2014).

According to Castells (2000) network can be considered as a set of interconnected “nodes”. Networks are open structures capable of unlimited expansion, integrating new nodes in multiple connections. These links are constituted by the unity of objectives of their participants and by the flexibility of these relationships. For Latour (2012), when Castells uses the term network, the meaning is that of the technical network, that is, where things pass, they are mixed with the organizational meaning of a network, since there is a privileged mode of organization due to the reach of information technology.

The network that makes up the Actor-Network Theory (ANT) does not designate an external object with the approximate shape of interconnected points, such as a telephone, a highway or a sewer network (Latour, 2012) . This network, which is part of the ANT, is not where things go, but what is formed in relationships. For the author, when weaving a network as an Actor-Network report, a series of actions are being developed in which each participant is recognized as a complete mediator, that is, he/she is causing changes and not just observing what happens around him/her.

Such a theoretical-reflective position, for example, can only be considered a good Actor-Network report if it is capable of provoking changes in those who read it, stirring the curiosity of teachers, and motivating them to build networks (concepts and not things) with their students. Otherwise, this text will only make translations or mere displacements of theories, without transforming them into practical actions, in short, an intermediary between the author and the title of doctor.

Thus, like the network, for ANT it is not where things go, the social is not what “hosts” associations, but what is produced by them. What about digital social networks? What is their connection with the so-called sociotechnical networks of ANT? For Callon (2008), one of the ANT scholars, there is a difference between social networks and the so-called sociotechnical networks, which, in turn, refer to the concept of the expression “actor-network”.

About this, the author states that social networks are configured by identifiable points and relationships; differently, in sociotechnical networks, we want to know the translations and the things that move between the points. The important implication in the sociotechnical network resides in the fact that one wants to know what is transported between the points, to know how the displacements are and how they occur, what is circulating, to appreciate what is at stake, what is being manufactured as identity, the nature of what moves, etc. The theoretical focus and the methodology interested in what circulates allows us to know what social matter is made of and follow its dynamics. So, the idea of translation corresponds to circulation and transport, to everything that makes one point connect to another by the fact of circulation (Callon, 2008).

With this differentiation given by Callon (2008), we understand that digital social networks are pre-established connections in ubiquitous media and that sociotechnical networks are time and space at the same time, that is, it is what is formed in relationships. In other words, everyday social relationships are included in the digital space managed by ubiquitous media, and interactions, in these environments or outside them, build sociotechnical networks or not, since many friends never interact with each other. These interactions will be discussed later when the dynamics of these digital social networks will be addressed.

So far, it has been possible to explain the differences between digital social networks and the network comprising ANT, but what is the difference or fit between social media and ubiquitous media? For Recuero (2012), social media is a tool that allows the appropriation of sociabilities. According to Primo (2014), social media is a term used to refer to a large group of online services that allow interaction, collaboration, and group work.

As previously noted, the understanding of social network is not synonymous with “social network site”, but rather the associative movement of the circle of people to whom actors are or are connected, formed through interactions in ubiquitous media (which have their own characteristic elements), serving as a basis for connections to be made and information about them to be apprehended.

We understand, then, that social media have many characteristics which differentiate them from traditional media (newspapers, television, books, and radio), for example: social media do not have an end or a certain number of pages or hours, and their content can also be commented on, edited and even mixed by your audience.

Some users can create Mashups – which is a website or a web application that makes it possible to mix various contents, music, videos to create new formats – and recreate new content with a mixture of what has already been posted and made available on the internet. In this way, social media depend on people’s interaction, as it is from the discussion between them that the content shared through technology is constructed (Martino, 2014).

While these social media provide access to information, they are also communication media and by doing so, they make available a type of ubiquitous, pervasive and, at the same time, embodied and multiply situated communication that is beginning to insinuate itself into everyday objectives with embedded technology, the so-called internet of things (Santaella, 2013).

According to the author, a media and communication format is in the air that goes beyond conventionalities and can reach people through proximity, either through coexistence or through common interests, in real or virtual life, as it is ubiquitous, or that is, it is present everywhere, if the actors are connected.

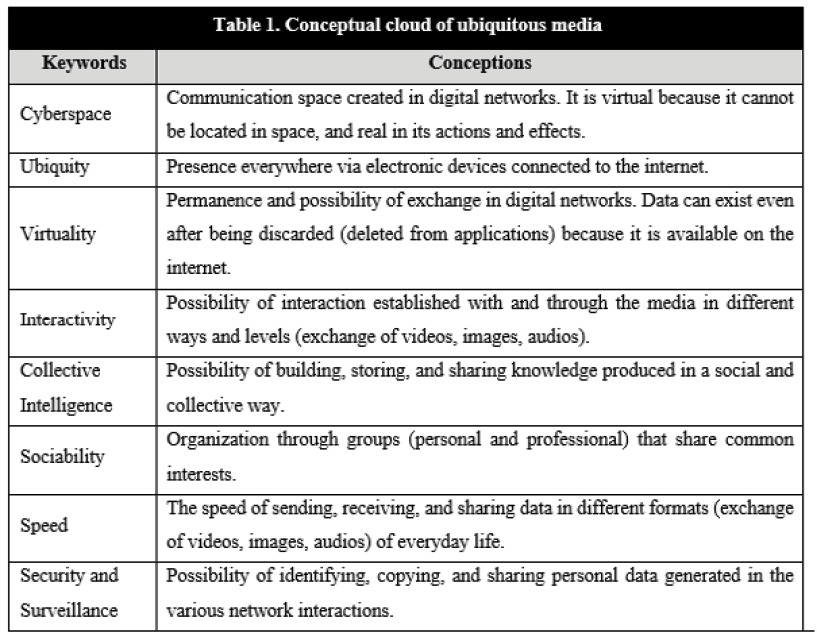

Based on this new media format, we understand that websites or applications that enable communication and simultaneous exchanges can be called ubiquitous media, precisely because of the ubiquity of cell phones, tablets, networks, and information. To assist in understanding ubiquitous media, we have organized some key concepts in Table 1, as follows.

Note: Translated from Schöninger (2017).

These elements corroborate an understanding of the structural dynamics of ubiquitous media from the communicational point of view. They point out that understanding the phenomenon of ubiquity and its applications is necessary so that one can enjoy the “omnipresence” of ubiquitous media in the daily lives of teachers and students, favoring the construction of learning networks, after all, the more access one has to information and knowledge, the more varied will be the opportunities for creating new learning.

To better understand the concept of ubiquity, we resorted to the explanation of De Souza e Silva (2006) which says that the concept of ubiquity alone does not include mobility, but mobile devices can be considered ubiquitous when they can be found and used anywhere. Technologically, ubiquity can be defined as the ability to communicate anytime and anywhere via electronic devices scattered throughout the environment. Ideally, this connectivity is maintained regardless the movement or the location of the entity.

The author continues stating that, of course, wireless technology provides greater ubiquity than is possible with wired media, many wireless servers, especially when on the go. In addition, many wireless servers scattered throughout the environment allow the user to move freely throughout the physical space always connected.

Within the Brazilian scenario, this connectivity has increased considerably from 2006 to the present day. Currently, with the affordable price of smarphones and the expansion of public spaces with Wi-Fi, more and more ubiquitous relationships are established.

These elements corroborate an understanding of the structural dynamics of ubiquitous media from the communicational point of view. They point out that understanding the phenomenon of ubiquity and its applications is necessary so that one can enjoy the “omnipresence” of ubiquitous media in the daily lives of teachers and students, favoring the construction of learning networks, after all, the more access one has to information and knowledge, the more varied will be the opportunities for creating new learning.

To better understand the concept of ubiquity, we resorted to the explanation of De Souza e Silva (2006) which says that the concept of ubiquity alone does not include mobility, but mobile devices can be considered ubiquitous when they can be found and used anywhere. Technologically, ubiquity can be defined as the ability to communicate anytime and anywhere via electronic devices scattered throughout the environment.

Ideally, this connectivity is maintained regardless the movement or the location of the entity. The author continues stating that, of course, wireless technology provides greater ubiquity than is possible with wired media, many wireless servers, especially when on the go. In addition, many wireless servers scattered throughout the environment allow the user to move freely throughout the physical space always connected.

Within the Brazilian scenario, this connectivity has increased considerably from 2006 to the present day. Currently, with the affordable price of smarphones and the expansion of public spaces with Wi-Fi, more and more ubiquitous relationships are established.

Results, discussion and conclusions

O We must agree with Lemos’ view (2013): at first sight, it seems strange to think of objects or things as mediators and that, therefore, do things, but they are interacting with humans on a daily basis: we wake up in the morning with our cell phone waking up, checking what the temperature will be like, the forecast of the weather, the traffic condition, then we check the messages received during the night and, while having breakfast, we check the news on Twitter, we take a “peek” into the lives of friends and “acquaintances” on Facebook and Instagram, such actions are the first ones developed by some people at the beginning of their day (LEMOS, 2013).

We can notice this convergence within school classrooms as well. In this context in which we are approaching, there is a constant evolution of languages in convergence, of movements and trends of a pedagogy that begins to realize that, according to Santaella (2013), we have become ubiquitous beings. We are both somewhere and outside of it. We intermittently become present-absent persons. Body, mind, and life ubiquitous (Santaella, 2013). Proof of this are the groups in instant messaging applications, made up of people from work, family, academics, children’s school, college, friends, best friends, in short, the list is endless. The fact is that we are in these spaces, and we are always in demand, and this conveys a sense of omnipresence.

In this way, while these groups bring people together and streamline their communicability through languages in convergence and between the various actors that are part of this digital everyday life, they also bring, due to their omnipresence, several side effects to privacy. That is why it becomes increasingly necessary to discuss such technological adoptions and their digital media internally and externally to the school space so that one learns to live in and with the “perpetual presence, from near or far, always presence” in the ubiquitous media.

The essay we wove with concepts that are not very close to research in the educational field, enabled us to show that with the elements of a network such as an Actor-Network report, it is possible to develop a series of actions in which each participant can be recognized as a complete mediator, that is, an actor who provokes changes and not just observes what happens around him/her and in his/her context.

We also consider that such a theoretical-reflective approach shows that we can only consider a good Actor-Network report if we are able to provoke changes in those who have access to our essay, reverberating and stirring the curiosity of teachers to, thus, motivate them continuously to build their own networks, interconnected or not, (concepts and not things) with their students in a full exercise of mediation and dialogue.

Finally, in the perspective of Educommunication and ANT, we describe the learning networks as associative movements whose actions may allow the elaboration of dynamics that potentiate the formation of educomunicative ecosystems, that is, spaces that are open, dialogic, collaborative, cognitive and communicative among the various actors that are part of the school community.

Referências

Aparici, R. (2012). Comunicação e web 2.0. In: R. Aparici (Org.), Conectados no ciberespaço (pp. 25-36). Paulinas.

Castells, M. (2000). A sociedade em rede. Paz e Terra.

Callon, M. (2008). Entrevista com Michel Callon: dos estudos de laboratório aos estudos de coletivos heterogêneos, passando pelos gerenciamentos econômicos. Sociologias, 19, 302-321. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-45222008000100013

De Souza e Silva, A. (2006). Do ciber ao híbrido: tecnologias móveis como interfaces de espaços híbridos. In: D. Araújo (Org.). Imagem (ir)realidade: comunicação e cibermídia (pp. 21-51). Sulina.

Latour, B. (1994). Jamais fomos modernos: ensaio de antropologia simétrica. Editora 34.

Latour, B. (2005). Reflexões sobre o culto moderno dos deuses fe(i)tiches. Universidade do Sagrado Coração.

Latour, B. (2012). Reagregando o social: uma introdução à Teoria do Ator-Rede. Universidade Federal da Bahia.

Latour, B. (2016). Cogitamus: seis cartas sobre as humanidades científicas. Editora 34.

Lemos, A. (2013). A comunicação das coisas: teoria Ator-Rede e cibercultura. Annablume.

Lemos, A., & Pastor, L. (2016). Internet das coisas, automatismo e fotografia. In: A. Lemos (Org.),. Teoria Ator-Rede e estudos da comunicação (pp. 103-124). Universidade Federal da Bahia.

Martino, L. (2014). Teoria das Mídias Digitais: linguagens, ambientes, redes. Vozes.

Oliveira, K., & Porto, C. (2016). Educação e teoria ator-rede: fluxos heterogêneos e conexões híbridas. Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz.

Primo, A. (2014). Industrialização da amizade e a economia do curtir: estratégias de monetização em sites de redes sociais. In: L. Oliveira, & V., Baldi (Orgs.). Insustentável leveza da Web: retóricas, dissonâncias e práticas na Sociedade em Rede (pp. 109-130). Universidade Federal da Bahia.

Recuero, R. (2012). A conversação em rede: comunicação mediada pelo computador e redes sociais na internet. Sulina.

Recuero, R. (2014). Redes sociais na Internet. Sulina.

Santaella, L., & Lemos, R. (2010). Redes sociais digitais: a cognição conectiva do Twitter. Paulus.

Santaella, L. (2013). Comunicação ubíqua: repercussões na cultura e na educação. Paulus.

Schöninger, R. (2017). Educomunicação e Teoria Ator-Rede: a tessitura de redes de aprendizagem via mídias ubíquas. [Doctoral thesis]. https://bit.ly/3cKBO0y