The consumption of clothing by millennials in the context of convergence between analog, digital and post-digital

El consumo de ropa de los millennials en el contexto de convergencia entre lo analógico, lo digital y lo posdigital

Mariângela Machado Toaldo

Universidad Federal do Ria Grande do Sul:

Departamento de Comunicación - Facultad de Información y Comunicación

E-mail: mariangela.toaldo@ufrgs.br

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7220-1475

Jane Aparecida Marques

Universidade de Sao Paulo

E-mail: janemarq@usp.br

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2382-9041

Fecha de envío: 03/06/2024

Abstract

This paper aims to analyze how the analog, digital and post-digital perspectives are manifested in some stages of the purchasing decision process of Brazilian millennials living in the cities of Porto Alegre and São Paulo, in relation to clothing consumption behavior. The data presented reflects the qualitative part of the research “Attitudes to buying and consuming certain goods and services among young people aged between 18 to 35 belonging to Generation Y: the influence of commercial advertising on decision-making”, carried out by Red Iberoamericana de Publicidad. This is an exploratory, qualitative investigation, supported by theoretical and empirical research, using the techniques of in-depth interviews and content analysis. The results point to a convergence of analog and digital media according to what is offered to the experience of young people, indicating signs of values corresponding to post-analog.

Keywords: analog; digital; post-analog; consumption; millennials.

Resumen

En este texto nos proponemos analizar cómo las perspectivas analógica, digital y posdigital se manifiestan en algunas etapas del proceso de decisión de compra de millennials brasileños, residentes en las ciudades de Porto Alegre y São Paulo, en relación con los comportamientos de consumo de ropa. Los datos presentados reflejan la parte cualitativa de la investigación “Actitudes de compra y consumo, de determinados bienes y servicios, de jóvenes entre 18 y 35 años pertenecientes a la Generación Y: influencia de la publicidad comercial en la toma de decisiones”, desarrollada por Red Iberoamericana de Publicidad. Se trata de una investigación exploratoria, cualitativa, sustentada en investigaciones teóricas y empíricas, utilizando técnicas de entrevista en profundidad y análisis de contenido. Los resultados apuntan a una convergencia de los medios analógicos y digitales según lo que cada uno ofrece a la experiencia de los jóvenes, indicando signos de valores correspondientes a lo post-analógico.

Palabras clave: analógico; digital; post-analógico; consumo; millennials.

Fecha de aceptación: 25/06/2024

Manuella Reale

Universidad Federal de São Carlos

E-mail: manureale@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7663-4550

DOI: 10.26807/rp.v28i120.2129

Fecha de publicación: 30/08/2024

Introduction

In contemporary times, many authors have observed a return to the cultivation of experiences outside the digital environment (Humayun & Belk, 2020; Gensler, Neslin, & Verhoef, 2017), including the use of analog or non-digital objects. This movement is called post-digital, that does not mean denying its existence or its operating logic, since so many processes that are necessary for people’s daily lives depend on them or are more easily linked to them, and thus there is often no escape from it. Instead, it is thought to be a condition of hybridity in which the digital does not cease to be part of people’s lives, but there is a (re)valorization of analog objects and practices (Humayun & Belk, 2020).

In this study, the purpose is to analyze how the analog, digital and post-digital perspectives are manifested in some stages of the purchase decision process of Brazilian millennials, university students, living in the cities of Porto Alegre and São Paulo, in relation to the consumption behaviors of clothing products. The data shown reflect only the qualitative part of the research “Attitudes of purchase and consumption of certain goods and services, of young people between 18 to 35 years old belonging to Generation Y: influence of commercial advertising on decision-making”, of Red Iberoamericana de Publicidad.

Millennials, since their childhood, have had contact with digital technologies, becoming the first generation to have an affinity for the use of these technologies in everyday life (Romero et al., 2023), and it appears that the changes provided by the internet directly interfered with the constitution of their identities and expressions (Urresti, 2008). Their immediacy and more critical view of the world around them, due to permanent and uninterrupted access to information, are examples of this influence. However, our research data pointed to a significant consideration of offline consumption environments, which has piqued our curiosity to understand what drives millennials to these environments, despite being so familiar with the digital world. How do they relate to offline and online instances in their consumption practices? What attributes link these young people to these instances? Would it be possible for them to replace one with the other?

2. Frame of Reference

2.1 From Analog to Digital and Post-Digital

Technological culture (Mazer & Nascimento, in Proulx, Pereira, & Rosa, 2016), also called digital culture (Romero et al., 2023) or cyberculture (Urresti, 2008), is inherently connected with youth culture (Romero et al., 2023; Pereira, 2021; Proulx, Pereira, & Rosa, 2016; Pais, 2012; Urresti, 2008; Martín Barbero, 1990), the millennials’ relationship with the world and also how they structure their consumption behavior. Spontaneously, these individuals shape their reality based on virtual access, choosing (consciously or not) to use their digital tools for routine tasks, such as interacting with peers, studying, working, entertaining, and consuming. They perceive digital logics as facilitators of everyday processes, having the functions of other media used in media culture1 (Pereira, 2021) as complementary.

Digital is associated with what can be done/consumed online, such as access to the internet, social networks, and the devices themselves (Humayun & Belk, 2020; Gensler, Neslin, & Verhoef, 2017). According to the authors, post-digital, on the other hand, can be understood as a way of restoring the boundaries between digital life and physical/presential experience, especially in terms of transcending the constraints of being connected in the digital world: monitored privacy; dispersion of attention, and time with multiple, continuous and intense connections, interruptions to focus activities, etc.

This logic expands to consumption through the search for analog objects that involve “craftsmanship and tangible connection” (Humayun & Belk, 2020, p. 17) such as cameras, vinyl records, artistic and cinematographic artifacts.... Objects that bring with them a history of life with their users, bringing back memories of events and experiences, enabling a certain nostalgia for their experiences. In this sense, analogous objects are said to convey an idea of “humanity of their own” (Humayun & Belk, 2020, p. 3).

According to Berry (2015, p. 45), “the post-digital is, then, both an aesthetic and a logic that informs the re-presentation of space and time within an epoch that is after-digital, but which remains profoundly computational and organized through a constellation of techniques and technologies to order things to stand by”. As a counterpoint, a search for the possibility of mindfulness, slowness, pause and imperfection in everyday life resurfaces (Humayun & Belk, 2020).

As Berry (2015) points out, post-digital does not eliminate the contemporary technical and technological environment. Thus, it is understood that digital environments have also become a place for expressing identity, carrying symbols to express opinions and experiences, validating groups and broadening connections between peers. Our research highlights the significance of new ways of being together (Martín Barbero et al., 2017), the construction of identity through digital media, and the interaction and consideration of others in the consumption process of millennials. Additionally, they seek out analog environments, offline, or physical stores for experimentation.

Other factors driving change in this scenario are the possibility of choosing the content to be consumed, making the consumer profile more restricted, the so-called niche content. It is also recognized that there is a movement to create free environments of their own, with a global reach, to express opinions on different topics, promoting horizontal relationships between individuals, groups, and brands. This has ultimately forced a change in the communication transmitted by other media and physical consumer environments in order to remain relevant in the contemporary world. In fact, Sbardelotto (in Proulx, Pereira, & Rosa, 2016, p. 149) indicates that “digital mediatization points to a context of remodeling the media landscape, which permeates and is permeated by several other social processes [...]”.

2.2 Hybrid Consumption: webrooming and/or showrooming

The consumption behaviors, according to García Canclini (2002), are inextricably linked to the development of identities and social meanings, emphasizing the importance of symbolic value over use and exchange values. In the author’s view, consumption is the indicative of an understanding of subjects’ identities and the ways in which the media are linked to the world of culture. Martín-Barbero (2009) also states that consumption is an activity that goes beyond the mere reproduction of forces and is related to the production of meanings. Consumption is seen as a battlefield that goes beyond the mere possession of objects, since their importance is determined by the uses assigned to these objects in the social sphere. Such uses include demands and strategies for action that derive from a variety of cultural competencies.

Consumption therefore reveals cultural traits of a society. In this sense, Montúfar (2011) draws attention to the dimension of the “moral economy”, made up of a set of principles, fundamental values, norms, and moral considerations that, in one way or another, are present while consuming goods, media and their content. Montúfar argues that new meanings and forms of expression of citizenship are emerging in consumer practices, especially when it comes to a communicative, more active, and informed citizenship in the public sphere. Based on these authors’ views, through consumption it is possible to understand millennials’ expressions of the post-digital perspective and the transit between digital and offline analog, their demeanor, and the meanings they find for each of them.

Gensler, Neslin and Verhoef (2017) have more precisely investigated the impact of search channels for consumer goods on consumer decision-making, both in offline physical shops and online retailers. This definition inspired us to think of physical purchases as an offline and analog mode, and purchases in the digital media as online. Designating them as such, in the contextualization of our data, indicates a coherence for reflecting on the post-analog. Considering the physical environment as analog would be to conceive it as a channel of information and consumption that does not involve computational and digital technology to exist, therefore its categorization as offline, as suggested by Gensler, Neslin and Verhoef (2017). In addition, it offers tangible connections with the shop experience, the product, the seller, and other consumers who are in the location (Humayun & Belk, 2020). Humayun and Belk (2020, p. 17) also relate the term “analog work” to post-digital, referring to the environment that involves human work different from virtual connections. This perception reaffirms the physical shop as an analog environment, which offers human work in contrast to virtual assistants and robots that serve consumers in the digital environment.

Flavián, Gurrea and Orús (2019), in turn, also researched purchase channels and their relationship with the satisfaction resulting from the purchase process. They analyzed purchases in a single channel (online or physical) and the processes of webrooming (consumer searches on the internet and then purchases in the physical shop) and showrooming (consumer sees the product in a physical shop and purchases over the internet). The results showed that cross-channel purchases predominated over single-channel purchases in all conditions. Webrooming not only leads to greater satisfaction, but also boosts consumer confidence.

Complementing these findings, Flavián, Gurrea and Orús (2020) demonstrated that webrooming makes consumers realize that they are saving time and/or effort and making better choices compared to showrooming. In addition, webrooming leads consumers to attribute the results of their purchases to themselves, increasing the feeling of being experienced buyers. However, showrooming makes consumers believe more strongly that they are making the right purchase, compared to webrooming.

These findings coincide with the data found in the research by Gensler, Neslin and Verhoef (2017). The authors have shown that physical shops have an advantage over showrooming by providing salespeople, an expectation of quality in their products, and speeding up the process of buying and collecting the product, thus satisfying the consumer’s time-saving needs as opposed to the disadvantages of the cost of online research and the dispersion of online prices associated with showrooming. On the other hand, better product quality and price conditions are the attractions of online consumption (Gensler, Neslin, & Verhoef, 2017). In addition to these latter aspects, Koscak’s research (2023) examined the custom of browsing fashion retail websites and applications, as well as the influence of publicizing fashion articles on social media.

In the contemporary context of immediatism, Kotler and Keller (2018) observed that the immediate need for things is mainly caused by external stimuli, such as the store environment, a social circle trend and/or the brand. In this context, the authors highlighted the importance of the point of sale as a facilitator for the contact with the product, gathering information, and making the purchase. Based on the authors’ advice that the simpler the process, the more likely it is to be converted into a purchase, it can be understood that visiting a physical shop provides the benefit of experience - trying on different sizes of clothing, appreciating whether the piece looked good on their own body, checking the fit, color, and other details. Other unique characteristics of the physical environment include immediate access to the product and interaction with sellers, who can provide guidance and answer immediate questions (Zhang, Chang, & Neslin, 2022; Gensler, Neslin, & Verhoef, 2017).

3. Methodology

The data presented here are results in line with the research of the Red Iberoamericana de Publicidad, whose objective is to analyze the variables that influence these millennials’ purchasing decisions in relation to clothing consumption. This process was investigated in its first four stages2: recognizing the need; searching for information; evaluating pre-purchase alternatives; and purchasing.

It is a qualitative exploratory study in nature, supported by theoretical and empirical research3, with the technique of in-depth interviews. This investigation is limited to observing the behavior of millennial generation, those born between 1980 and 2000 (Tanyel, Stuart, & Griffin, 2013), also known as Generation Y.

The sampling technique adopted was non-probabilistic by convenience, totaling 36 respondents4, all undergraduates, half from Porto Alegre (POA) and the other part from São Paulo (SP) and by quotas:

• age group5: 18-23 year olds, 24-29 year olds, and 30-35 year olds;

• socioeconomic level: simplified version of the Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria, updated by ABEP (2018): upper average income (Classes A, B1, and B2) and low average income (Classes C, D1, D2, and E);

• gender: male and female.

The collection instrument used was prepared by Red Iberoamericana de Publicidad. Three (3) pre-tests were carried out for validation. All interviews were conducted remotely, using the Google Meet video call platform.

For data analysis, it was adopted the parameters outlined by Bardin (2002) for content analysis, understood as a set of techniques whose objective is the search for the meanings manifested by the interviewees.

4. Results

The answers obtained in the interviews were analyzed to understand the means of initial exposure to clothing products (4.1), decision-making factors (4.2), and sources of information (4.3) that modulate the participants’ purchasing decisions. The aim was to find out how the need is recognized (based on the means of first contact with the product), the search for information (which means of information the product was searched for before the purchase); the evaluation of pre-purchase alternatives, and the purchase (based on the purchase decision factors).

The analysis of each question related to the topic of clothing resulted in a word cloud that listed the main responses among the interviewees. The hierarchy graph shows the grouping of answers according to the variables of age group, socio-economic level, and city of residence.

4.1 Recognizing the need - first contact with the product

When questioned about where they first saw the product, a variety of responses were observed. Some participants mentioned seeing the product in physical shops, while others found it on social networks.

Figure 1: Word cloud in relation to the media where they first saw the product before buying it

Source: Prepared by the authors using NVivo software, version IV.

As seen in Figure 1, the most common ways people first saw the item were physical and at the mall, followed by digital media such as social networks, Instagram, and the internet. When it came to millennials’ initial contact with a product, physical media prevailed over digital media.

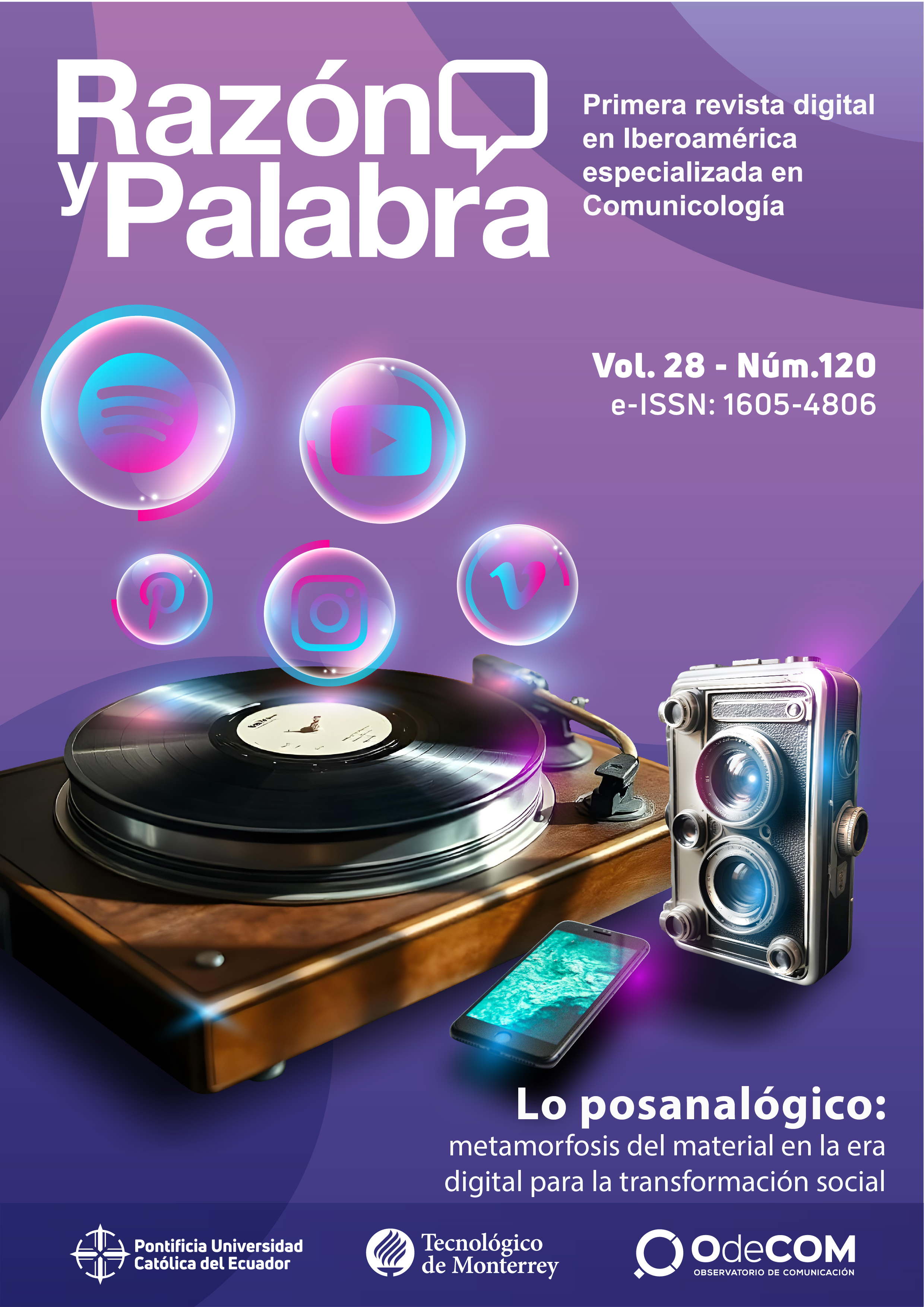

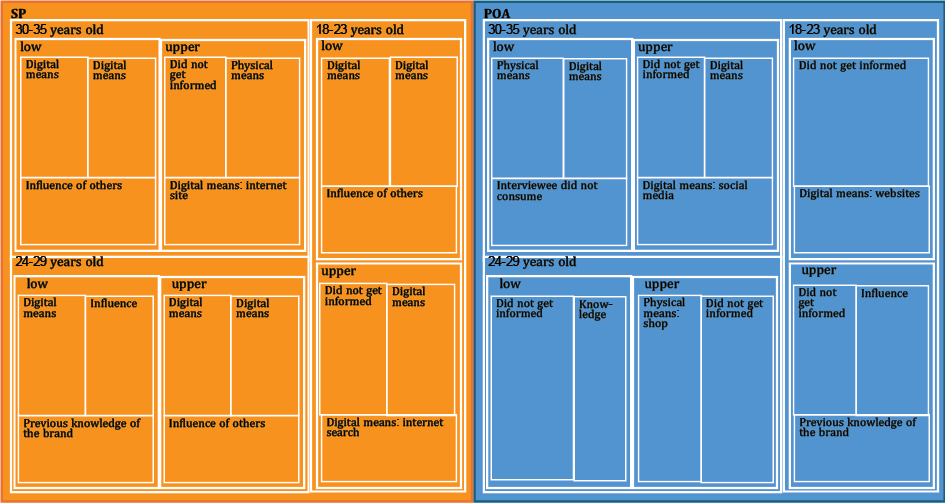

Figure 2: Hierarchy of Information Search for Clothing Purchase

Source: Prepared by the authors using NVivo software, version IV.

Figure 2 above shows the same behavior for the profiles surveyed. The only group to indicate only digital means was that of millennials aged between 30 and 35, with upper average income, from Porto Alegre.

The “Fashion Consumption 2023” survey (Koscak, 2023) observes that Brazilian consumers who prefer to shop in a physical shop do so because they can try on the product and check its quality, it is convenient to leave with it in their hands, it’s easy to return it if necessary, and “because going to the shop is a leisure activity” (Koscak, 2023, n.p.).

In this survey, millennials expressed another benefit of physical location: the emergence of an opportunity to consume in an environment they are already used to visiting, as seen in the comments of participants 11: “I was just walking around the shopping mall and decided to buy”; 23: “I went to the market I’m used to”; 05: “I went straight to the shop where I normally consume the products, so I saw the clothes and bought them”.

The physical shop was particularly relevant since it is part of the context in which millennials live, and they regard it as a channel for accessing and shopping for things. It offers immediate contact with the product, allowing for a full sensory experience: customers can touch and try on the clothes before making a purchase decision. These factors provide a more accurate assessment of the quality, fit, and comfort of the product, something that is not possible when shopping online (Delemazure, Mallégol, & Laplanche, 2018). This contact with the product in the physical environment strengthens confidence in the purchase (Flavián, Gurrea, & Orús, 2019) and can encourage spontaneous purchasing decisions, as evidenced in the statement by participant 32: “During my lunch breaks when I’m passing by the city center, I always see something that catches my eye and I buy it. Even if I do not need it”.

In contrast, at the secondary level of the cloud, digital was the most popular means for millennials. Through it, consumers consume advertisements and offers about the clothing product and can buy it, validating digital as an environment of information, influence, and market because it provides facilities to simplify the consumption process. The results obtained represent these motivations, such as the comments from participants 7: “[...] I prefer to go to a physical shop, but since the sales are more in online shops, I chose the online shops (for my last purchases)”; and 20: “Since I discovered Shein, I often buy directly from the app, sometimes I use other sites, but I usually buy online”.

Given that the majority of the mentions of the digital means were made by millennials with upper average income between 30 and 35 years old in Porto Alegre, who are generally already working at least 6-hour days, it is difficult for them to access physical shops due to commuting, distance, and time availability. As participants 25 says: “Because I can buy everything in one place on the internet without having to go out, that’s why I end up buying more digitally”; and 04: “Everything related to the internet. I saw the advert. I went to the website to see the reviews. After doing all this research, I bought it”.

A third level of cloud highlighted digital-specific factors: “survey,” “shopping websites,” “search,” “pinterest,” “instagram,” and “internet.” These quotations show the value of digital references. Millennials access social media platforms such as Pinterest and Instagram to consume styles, fads, and trends shared by their peers. Urresti (2008, p. 65, own translation) note that “to the extent that the Internet makes posting easier than ever before, this set of repertoires, which were previously sporadic or difficult to find, now has a level of simple and immediate accessibility at a low cost”, to which millennials want to contribute to the construction of their identities.

The development of this identity is expressed not only by relationships between millennials, but also by the consumption of goods and services that signal belonging in a specific group. Martín Barbero et al. (2017) found that the market has monetized the value of identity through affordable items for millennials. As a result, millennials’ initial engagement with the product can stem from their need to express themselves and belong.

4.2 Purchase decision factors

As for the factors that led to the purchase decision, the need and quality of the product stood out, highlighting specific characteristics that convinced millennials of its usefulness or value. Others mentioned promotional value and social influences, such as recommendations from friends or digital influencers, as key determinants in their purchasing decision.

Figure 3: Word cloud with the factors that led respondents to decide to purchase clothing

Source: Prepared by the authors using NVivo software, version IV.

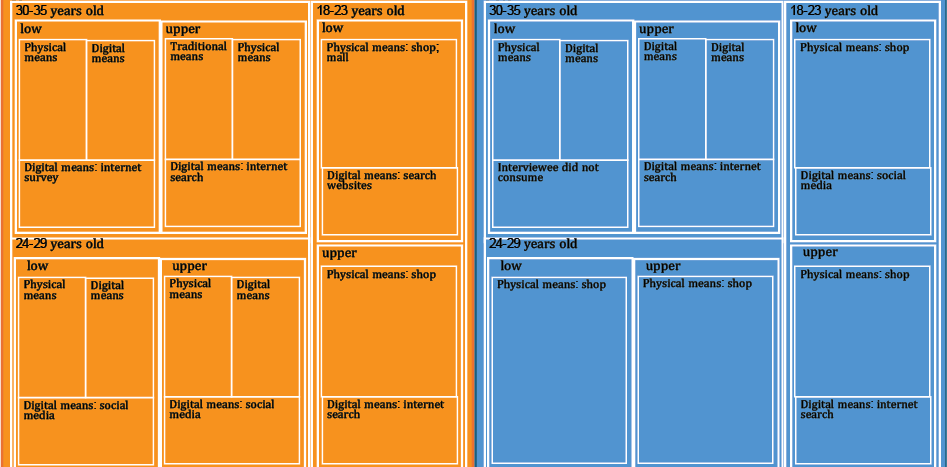

Figure 4 shows the hierarchy of purchasing decision factors, respectively: needs, price/sales, and quality/specificities.

Figure 4: Hierarchy of purchasing decision factors for clothing items

Source: Prepared by the authors using NVivo software, version IV.

Need emerged as the main factor for the low average income groups aged 30-35 in both cities, and for the upper average income millennials in the same age group in Porto Alegre, as well as for the low average income millennials aged 24-29 in Porto Alegre, and the upper average income millennials in São Paulo.

Price/Sales were indicated by low-income 18-23-year-olds in São Paulo and Porto Alegre, while upper-income 18-23-year-olds and 24-29-year-olds in Porto Alegre did the same. Possibly, younger individuals rely on their parents for financial support or earn lower salaries when they work.

Quality and/or specificity were factors for millennials in São Paulo, for the 18-23 age group, with upper average income, and the 24-29 age group, with low average income.

It was evident that the primary motivator for the purchase is the necessity for the product. It can be interpreted from two perspectives: one rational, referring to a lack, and the other as a desire to purchase. The need driven by the lack was indicated by participants 2: “[...] I needed winter clothes”; and 14: “I needed to buy clothes”, were statements that correspond to the results of Koscak (2023). In this survey, 24% of Brazilian consumers bought a clothing item because it got cold and they needed warm clothes, while a further 21% bought because their old clothes were too old. The fact that the millennials who indicated need as a factor for their purchase were of low average income (24-29 year olds in Porto Alegre and 30-35 year olds in both cities), but also of upper average income (24-29 year olds in São Paulo and 30-35 year olds in Porto Alegre) may reveal that the latter ultimately decides on making a more conscious, one-time purchase.

The other interpretation is a desire fueled by the logic of consumption, as shown in the cloud (Figure 3) by motivating source terms such as “others,” “taste,” and “desire.” According to Koscak (2023), 26.2% of clothing purchases in Brazil were made as part of the interviewees’ repeated consumption practice, regardless of their necessity for the items.

One aspect that stimulates millennials’ desire are reference groups, represented in Figure 3 by the terms “influence” and “others”. This is related, according to Proulx, Pereira and Rosa (2016, p. 113), to “informational capitalism”, which sees the emergence of a contributory economy based on group exchange. The exchange becomes tangible through products or services that carry a symbolic value required by the parties who will share this asset among themselves, in order to influence the formation of the individual identity of each person in the social group. Koscak’s research (2023) reinforces this understanding by indicating that “78% of people express themselves and communicate with the world through fashion”.

According to Figure 4, the “quality/specificity” of the product remained an essential component in persuading millennials to buy, indicating that they may consume them primarily for the benefit provided. Blackwell, Miniard and Engel (2000, p. 137) state that the degree of importance attributed to a brand name, or a specific product depends on the consumer’s ability to identify attributes associated with the notion of quality. Notably, even the less prominent factors in the cloud (Figure 3), such as “comfort”, “fit”, and “brand”, refer to the qualities perceived by the consumer about the product, the first two of which are more easily identified in physical shops.

Figure 3 shows that price/sales is the most prominent secondary factor. According to Kotler and Keller (2018), the combination of price and product or service quality is what creates value. As a result, price and advertising are extremely important to consumers. In the study, these factors were significant mostly for millennials aged 18-23 with low average income in both cities, and for those aged 18-23 and 24-29 with upper average income in Porto Alegre. Despite their upper income, even millennials consider price and sales when making a purchase, indicating a more conscious idea of consumption. Thus, it can be understood that consumers not only need to be able to pay the price of the product, but also to be willing to do so.

4.3 Searching for information about the product before the purchase

When asked how the participants found out about the product, they revealed a diverse range of behaviors. Many mentioned that they had searched on websites, visited the shop, or got information from others.

Figure 5: Word cloud on how respondents found out about the product before buying it

Source: Prepared by the authors using NVivo software, version IV.

Digital searches, the internet, websites, and physical shops are the most common sources of information used by millennials prior to making a purchase.

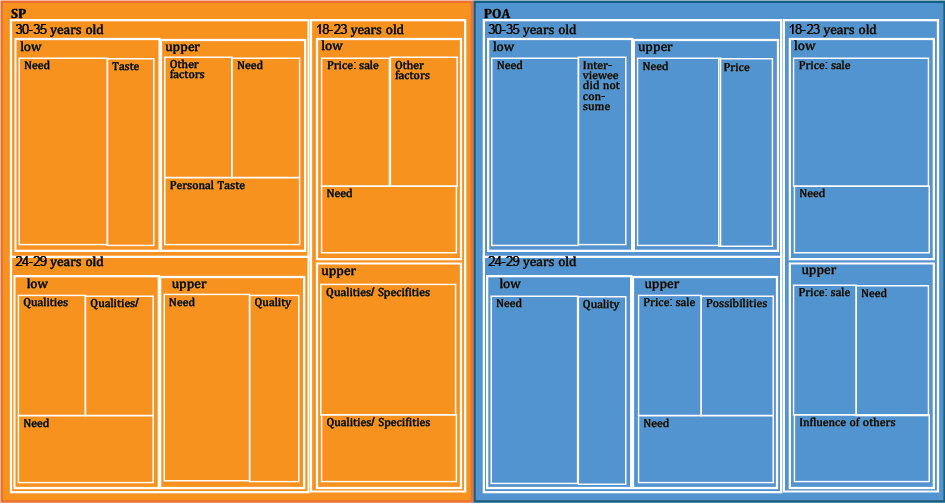

Figure 6: Hierarchy of means of searching for information before buying clothing items

Source: Prepared by the authors using NVivo software, version IV.

Figure 6 depicts the behavior of the two cities can be distinguished in terms of means. In São Paulo, millennials looked for digital means or did not get informed. In Porto Alegre, physical means were prioritized, or they did not get informed either.

Digital means were the source of information for all millennials with low average income and those aged 24-29 with upper average income in São Paulo. The 30-35-year-olds and the 18-23-year-olds with upper average income in the same city, on the other hand, did not get any information. In Porto Alegre, the low average income groups aged 18-23 and 24-29 years old; the upper average income groups aged 30-35 and 18-23 years old also did not get informed. The low average income 30-35-year-olds use physical means, the same behavior as the upper average income 24-29-year-olds.

Although Figure 5 highlights the terms “means” and “digital”, it also shows the term “shop” at a secondary level, referring to the “physical” environment. This represents the two spheres in which millennials say they get information about the product. This result reveals the complementarity between the physical, offline shop, and the digital environment, as already shown in topic 4.1.

The terms in the cloud (Figure 5) “site”, “purchases”, “surveys”, “comments” and “reviews” prove that millennials use the digital means to search for products, compare prices, read reviews, and take advantage of the physical experience to try on different types and sizes of clothes, and also appreciate the fit of the garments on their own bodies (Delemazure, Mallégol, & Laplanche, 2018; Gensler, Neslin, & Verhoef, 2017). This indicates that even in a global society, there are certain particularities in the construction of the environments in which we live. The millennials’ statements reaffirm such particularities: participants 18: “I think that, for me at least, clothes, in the sense of shirts, shorts, trousers, things like that, have to fit the body. But it’s a lot more than looking. I need to see, touch the fabric, touch things”; 31: “I usually see clothes in the shop. And the rest, anything else, I see online”; 19: “Accessories [I buy] online. Clothes and shoes directly in the (physical) shop”; 13: “Mainly clothes. I’ve rarely seen any clothes that I couldn’t try on”.

5. Discussion

The interaction of physical, analog, offline, and digital means demonstrates that, even in an era when the digital environment offers itself as a facilitator of practices and consumption through virtual relationships, the offline, tactile, and concrete experiences remain important and valuable. The data demonstrates that millennials value interacting directly with their experiences, whether physically in consumer locations or during the purchasing process.

Although, contemporary circumstances increasingly demand more activities, responsibilities, and challenges from millennials, for whom the digital environment offers possibilities based on the functionalities it aggregates, which ultimately encourages them to concentrate their search for the resources needed.

The possibility of interaction between physical, analog, offline, and digital methods change the experience in each instance. The elements influencing millennial decision-making corroborate the reasons for first contact with the product and the search for information before purchasing in both physical and digital settings. Among these aspects, identifying the need and the quality/specificity of the goods may be more motivated by physical stores because of the external stimuli they provide (Kotler & Keller, 2018). Direct access to goods and the consumer environment, the possibility of tactile, visual, and olfactory experience with the product, the sales professional, and other people in the environment, as well as the immediate acquisition of information and possession of the product, all encourage millennials’ relationship with the physical, offline, analog environment of shops and motivate their consumption processes. On the other hand, the influence of others, reference groups, and the search for price/sales conditions can be found more easily in the digital environment because it offers a wide range of ways to promote information in this regard with a single access, without having to leave the places the consumers are (Delemazure, Mallégol, & Laplanche, 2018; Gensler, Neslin, & Verhoef, 2017).

This distinction between what is specific to each environment is not rigid and does not always occur independently; the processes are often interconnected. The purchasing process of some of the participants interviewed involves using more than one channel - webrooming or showrooming (Flavián, Gurrea, & Orús, 2019; 2020). Some search for products on the internet before visiting a physical shop, or vice versa.

Millennials’ identities have been substantially shaped digitally through social media, reference groups, and the influence of others, as well as by gathering in environments that provide content that contributes to their development. The same is true for the establishment of their communities, which employ virtual sites. This draws attention to the fact that social networks and peers have a greater impact on millennials’ purchasing patterns and identity formation than brands. Another key factor to consider is the importance millennials place on social contact. One example is the extension of experience exchange in the digital world, even virtually, through the highly valued search for references with peers or others, not only about products, but primarily about experiences shared by and with others. This does not mean that offline, face-to-face relationships do not take place, but that they are not always possible, and the virtual world favors these processes by offering a range of information in the same place without the need to commute, as mentioned by the youth in their speeches. Sbardelotto (in Proulx, Pereira, & Rosa, 2016) observes that the mutual relationship built between technological innovation and the social environment has forged a new scenario of interaction.

One notable fact is that millennials prefer to buy clothes offline, which also pertains to the manifestation of their identity through authenticity, as they emphasize the importance of trying on garments to see how they fit on their bodies. As much as they absorb knowledge and trends in the digital world to help them construct their identity, they recognize the need of validating them on their own bodies. The references may be numerous, but the importance of tailoring them to the individuality of the young person remains, as does their personal touch in consuming. Authenticity and originality are hence other criteria that support the interaction between the analog and digital world (Humayun & Belk, 2020).

Furthermore, maintaining the habit of visiting physical, analog shops means resisting the intense pace promoted by the digital age (Humayun & Belk, 2020), in which everything can be found in the same place without commuting, but there is also a plethora of information competing for people’s attention/focus and fragmenting their time. The attitude of going out to explore an offline consumer environment - shopping malls, shops, fairs, etc. - demonstrates a use of time that is insubordinate to contemporary logic, less fast and instantaneous, it also evidences someone enjoying time, spaces, and consumables in an analog way, taking advantage of the experiences they can provide, including face-to-face interactions.

6. Conclusion

Initially, the aim was to investigate how the analog, digital, and post-digital perspectives are manifested in some stages of the purchasing decision process of Brazilian millennials, as a result of their major consideration of offline consumption environments. The following questions were raised: what drives millennials to these environments, despite being so familiar with the digital world? How do they relate to offline and online environments in their consumption practices? What attributes link these millennials to these environments? Could they substitute one for the other?

The analysis of this paper answered these questions. The experience of their interviewees showed how they integrate digital, analog, and physical processes, indicating the contributory aspects of each instance in their purchasing decision-making processes and in their daily lives. In this context, there are indications that millennials are cultivating the idea of post-analog, even if it cannot be said that they are intentional and conscious. These signs can be seen in the appreciation of what is analog in physical environments: direct contact in their experiences with products, with offline physical environments (shops), and with others (salespeople, consumers, peers, etc.) (Gensler, Neslin, & Verhoef, 2017), through touch, sight, smell, and hearing, which favors “tangible connections” (Humayun & Belk, 2020, p. 17). Another manifestation of the notion of post-analog is the preservation of the values of authenticity, individuality, and the use of time for face-to-face experiences, regardless of trends proposed by others and contemporary immediatism.

Finally, there is consistency in the concept of media convergence, discussed by Pereira (2021), Proulx, Pereira and Rosa (2016), Urresti (2008) and Jenkins (2006), when observing the young millennials surveyed. It introduces the concept of coexistence, complementarity, and hybridism (Humayun & Belk, 2020) between the physical and digital environments, in which the physical has not been supplanted by the digital, nor will the analog replace the latter, regardless of how much the post-digital gains conscious adhesions. It is about the complexities of living outside of the techniques and technology that shape our lives in many aspects, yet the value of personal, direct, concrete, non-virtual connections with objects, experiences, others, and ourselves persists.

7. References

ABEP – Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (2018). Alterações na aplicação do Critério Brasil: valid from 2018, April 16th. São Paulo: ABEP.

Bardin, L. (2002). Análisis de contenido (3rd ed.). Madrid: Akal.

Berry, D. M. (2015). Postdigital constellation. In D. Berry & M. Dieter (Eds.). Postdigital aesthetics: art, computation and design (pp. 44-57). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Blackwell, R.D., Miniard, P.W., & Engel, J.F. (2005). Consumer Behavior. 10th ed. USA: SouthWestern: Thomson Learning.

Delemazure, O., Mallégol, O., & Laplanche, V. (2018). The effect of the senses on consumers experience in clothing stores. AUTEX Research Journal, 23(3). https://doi.org/10.2478/aut-2022-0016.

Erikson, E. H. (1976). Identidade, juventude e crise (2nd ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Zahar.

Flavián, C., Gurrea, R., & Orús, C. (2019). Feeling Confident and Smart with Webrooming: Understanding the Consumer’s Path to Satisfaction. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 47(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2019.02.002.

Flavián, C., Gurrea, R., & Orús, C. (2020). Combining channels to make smart purchases: The role of webrooming and showrooming. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101923.

García Canclini, N. (2002). Consumo cultural: una propuesta teórica. In G. Sunkel (Ed.). El consumo cultural en América Latina: Construcción teórica y líneas de investigación. Santa Fe de Bogotá: Convenio Andrés Bello.

Gensler, S., Neslin S. A., & Verhoef P. C. (2017). The Showrooming Phenomenon: It’s More than Just About Price. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 38(2), 29-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2017.01.003.

Humayun, M., & Belk, R. (2020). The analogue diaries of postdigital consumption. Journal of Marketing Management, 36, 633-659. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1724178.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York: New Yor University.

Kotler, P. & Keller, K.L. (2009). Marketing Management. London: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Koscak, G. (2023). Pesquisa interna Globo: Consumo de Moda 2023. Offerwise Jun/23. Sales Insights, Sales Excellence. https://gente.globo.com/o-consumo-de-moda-e-o-potencial-brasileiro/.

Martín-Barbero, J. (1990). Cuadernos de comunicación y prácticas sociales: Reflexiones en torno a su investigación. México: Universidad Iberoamericana.

Martín-Barbero, J. (2009). Dos meios às mediações: comunicação, cultura e hegemonia. Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ.

Martín-Barbero, J. et al. (2017). Jóvenes: entre el palimpsesto y el hipertexto. Barcelona: NED.

Montúfar, F.C. (2011). De la “recepción” al “consumo”: una necesaria reflexión conceptual. In Jacks, N. (Coord.) Análisis de recepción en América Latina: un recuento histórico con perspectivas al futuro (pp. 13-17). Quito: Ciespal.

Pais, J. M. (2012). Sexualidade e afectos juvenis. Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. Lisboa: ICS. Imprensa de Ciências Sociais.

Pereira, S. (2021). Crianças, Jovens e Media na Era Digital: Consumidores e Produtores? Braga: CECS, UMinho Editora.

Proulx, S., Pereira, J., & Rosa, A.P. (Orgs.) (2016). Midiatização e redes digitais: os usos e as apropriações entre a dádiva e os mercados. Santa Maria, RS: FACOS-UFSM.

Romero, E. et al. (2023). Viralizando el Desencanto: Juventudes, satisfactores inmediatos y el futuro que se consume. Toluca, Estado do México: Seminário Internacional sobre Estudios de Juventud en América Latina.

Sbardelotto, M. (2016). O “católico” em reconexão: a apropriação sociorreligiosa das redes digitais em novos fluxos de circulação comunicacional. In Proulx, S., Pereira, J., & Rosa, A.P. (Orgs.). Midiatização e redes digitais: os usos e as apropriações entre a dádiva e os mercados (pp. 145-174). Santa Maria, RS: FACOS-UFSM.

Tanyel, F., Stuart, E. W., & Griffin, J. (2013). Have “Millennials” embraced digital advertising as they have embraced digital media?. Journal of Promotion Management, 19(5), 652-673.

Urresti, M. (Ed.). (2008). Ciberculturas juveniles: los jóvenes, sus prácticas y sus representaciones en la era de Internet. Buenos Aires: La Crujía.

Zhang, J.Z., Chang, C.-W., & Neslin, S.A. (2022). How physical stores enhance customer value: The importance of product inspection depth. Journal of Marketing, 86(2), 166-185.

1 The term refers to all screens used by the media for communication with the viewer/ user/ consumer.

2 The purchase decision making process, through the simplified model, is defined by Blackwell, Miniard and Engel (2005), in seven stages: Recognition of the need, Search for information, Evaluation of pre-purchase alternatives, Purchase, Consumption, Post-purchase evaluation, and Disposal.

3 The empirical research protocol was previously approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, according to CAAE 98430218.0.0000.5347, which can be checked at cepe@ufrgs.br.

4 For ethical reasons, the names were omitted to preserve the identity of the respondents.

5 According to the Statute of the Child and Adolescent – ECA – Brazilian (Law 8,069/90), the individual from 15 years old until reaching the age of majority, at 18, is considered young. Young adults, based on the view proposed by Erikson (1976), are individuals in the age group between 20 and 35 years old.