1. Introduction

In the midst of a communicational context in which false information circulates freely, especially on digital platforms, knowing which content (journalistic or not) to believe is a difficult task, given that fake news, is well constructed and aims to cause noise in communication, misinforming and misrepresenting public opinion.

Although fake news, in the aesthetic-enunciative form that popularized it in the digital context (Gomes & Dourado, 2019), is not something related to journalism, in contemporary times, a factor that has contributed to the dissemination of distorted information (Costa, 2009) is the speed with which journalism conveys it, often without going through rigorous checking. By publishing a piece of news without the scrutiny of the fact-check, the journalist in charge is exposing himself, putting the credibility of the press outlet, for which he is responsible, in danger, in addition to his own name at stake.

Within this context, Han (2022) argues that our current situation is the era of "post-truth", since the context of platformization (Van Dick et al., 2018) and content bubbles makes each person (or group) build their own reality apart from the others, contributing to believing only what confirms each one's beliefs. Meanwhile, Manjoo (2008) uses the expression "post-fact" when he wants to designate the potentiation of communicational noise, that is, disinformation, after all, anyone can create false news or take any information out of context; For this she only needs an electronic device.

In this view, it is pertinent to understand how journalism students perceive the future of the profession, since they will be the ones who will be working in the professional market in the coming years, considering a period in which fake news and disinformation directly affect journalism. In view of this, our study aims to understand how journalism students at the State University of Paraíba (UEPB), located in Brazil, evaluate the profession of journalism in relation to its relevance and what they expect from the area for the coming years.

Our article raised the following questions to students: How do you see the credibility of journalism today, in the midst of so much misinformation and fake news? Is there impartial journalism within this context? Would this much-idealized impartiality be the way for journalism to remain relevant? These are central questions of our research.

To obtain the answers, in addition to considering the studies in the area, we formulated questions and made them available via Google Forms to students over 18 years of age in the Journalism course at UEPB. 62 students participated in our research, which represents 13.21% of the students enrolled in the 2023.2 academic period. The questionnaire had 7 objective questions, whose answers we will discuss throughout the work, right after the literature review and methodological aspects.

2. Journalism, platforms and mediatization

When considering talking about journalism and its credibility in a scenario in which digital platforms have gained prominence in society (D'Andrea, 2020; Van Djick et al., 2018), it is necessary to reflect on how technically mediated relations intensify the process of deep mediatization (Hepp, 2020).

According to Martino (2019, p.17), "the idea of mediatization seems to be more powerful when thought of within a society in which the presence of the media, in any public space, is immediately visible". What is very clear, in contemporary times, is the growing number of connected users who share and interact in their personal profiles, exposing their points of view, which are not always well interpreted, taking into account that our messages, whether oral or written, allow different understandings by different people.

Meanwhile, Mintz (2019, p. 99) says that "[...] the concept of mediatization generically names the process of long-term social transformation resulting from a growing participation of the media in social life". Evidently, it is noticeable that the media, in their different formats and contexts, exert a strong influence on the formation of society's points of view, as they offer the necessary mechanisms for the compilation of essential knowledge when making the most varied decisions.

According to the studies of Hjarvard (2014, p. 25), “Mediatization is a reciprocal process between the media and other social domains or fields. Mediatization does not concern the definitive colonization by the media of other fields, but rather concerns the growing interdependence of the interaction between media, culture, and society.”

The process of mediatization is, therefore, interrelated with the various social interactions, and is so not homogeneous. Martino (2019) states that the notion of media, in studies on mediatization, is very diverse, and can refer, at the same time, to a set of technological devices, to an agglomeration of social, state or private institutions, and a specific form or language of elaboration of a message.

“In its first form, the media can be understood as the technological devices responsible for connecting people at varying degrees of distance. The focus is on the so-called "support" of the message considered in its materiality – from print to digital media. The presence, availability and use of these devices in daily life are decisive for the mediatization process.” (Martino, 2019, p. 23)

In order for the subject's message to be shared, it is necessary to have the help of the device with internet access for the entire process to be effective. This is the support that the author mentions above. However, this supposed democratization of access to the internet, especially with the advent of media platforms, has brought considerable problems to journalistic work.

Marcondes Filho (2019, p.17) mentions that it is necessary "[...] a concerned and radical reflection on this new phenomenon, a direct child of the accelerated replacement of technologies and their attachment to the strategies of supremacy and control of the political and economic forces of the planet". Undoubtedly, "at the same time that the media gained momentum as an institution in itself, the media became ubiquitous in almost all spheres of society" (Hjarvard, 2014, p. 30), especially through content shared on multiple digital platforms.

D'Andréa (2020, p. 13), explains that "throughout the 2010s, the so-called Big Five – Alphabet-Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook-Meta, and Microsoft – consolidated themselves as infrastructural services and today increasingly centralize daily and strategic activities".

“Influences on electoral processes, unrestricted use of personal data for commercial purposes, and the use of algorithms and databases to perpetuate prejudice and inequalities are some of the issues that increasingly concern governments, companies, and civil society. The revelation, in 2018, of the abusive use of data from Facebook by the company Cambridge Analytica can be taken as a milestone in the midst of a succession of scandals and uncertainties carried out by online platforms.” (D'Andréa, 2020, p. 13)

This technological context, of platformization and mediatization, affects journalistic practice directly: “It is in this ambience of the process of mediatization of society that we think of journalistic practice, which not only undergoes changes due to the development of new technologies or increasingly harsh demands of the labor market, but above all is affected by other logics of contact that are activated by its users/receivers/consumers/readers. New contracts are built between these instances, new rules are created and also other strategies are developed so that contact is expanded”. (Verón, 2012 as cited in Borelli, 2017, p. 37).

In this way, digital platforms use algorithms and direct a flood of information that meets the preferences of users in a subtle way, going unnoticed. These suggestions can be market products, political information, results of games of the preferred team, among other multiple subjects. In this logic, a potentially fake news can simply reach thousands and misrepresent public opinion when driven by algorithms.

3. Credibility and ethics in journalism

It is the function of journalism to make society have accurate information so that each individual can think, reflect and position themselves on what is happening in the world. The contents, the data, the interviewees are part of this story, contributing to the exercise of full and effective citizenship, subsidizing decision-making.

“By telling, remembering, retelling, recording, debating, polemicizing, journalism helps collective and individual memory to become social and historical, in addition to contributing to itself so that it is, like other areas, the memory of humanity. And to contribute so that such memory constitutes a reference for action, for opinion, for democracy and for the constitution of citizenship”. (Karam, 2004, p. 251)

According to Costa (2009), ethics refers to our everydat actions on a daily basis, being an unfolding of morality, a broader notion that is associated with culture. Ethics is individual and defines what is good or bad for oneself and for others. In this sense, ethics is something subjective, but it can also be normative, materializing in codes, such as the Code of the Brazilian Journalist.

Credibility, on the other hand, is the quality that the individual attributes to a certain product (in the case of journalism), based on objective and subjective notions. The perception of credibility depends on the entire repertoire, on the subject's cultural baggage (Souza Lima & Barbosa, 2023). This means that, even if a newspaper, report or even the entire media outlet has high technical quality, people may consider these products credible and others not. In a context of content bubbles and post-truth, this perception is increasingly diverse and antagonistic, with a drop in the credibility of journalism as a whole (Souza Lima & Barbosa, 2023), making it difficult to build common realities that enable rational dialogue (Han, 2022).

Care with the confirmation of information, that is, the veracity of what happened, has always been essential in journalism. The search for a truth as correspondence or conformity to reality about facts is one of the deontological principles of journalism (Lisboa, 2012; Trasel et al., 2018). Therefore, each professional who performs the function must follow, or at least it is expected, that he is ethical and respectful of the subjects conveyed and the actors involved in the stories.

It should also be noted that the credibility of journalism has been affected on a large scale in recent years. Many people understand that fake news is produced, in general, by journalists (Gomes & Dourado, 2019), which is not true. Another fact that contributes to the credibility crisis is the occurrence of attacks by politicians against journalists. The accusations reverberate in digital media and go viral. This disinformation circulates frequently and is shared, in most cases, by groups of partisan fanatics who live in bubbles. They are the ones who repeat speeches and share dubious material, sometimes even knowing that they are lies.

In this way, we understand the real relevance of journalism, especially in its construction. Journalism is committed to informing people of the facts as they happened or as close as possible, ascertaining opinions from different positions, giving plurality and voice to those who do not have one, highlighting invisible people and denouncing the darkest cases that anyone can imagine. This is the true role of the serious journalist committed to events (da Silva & Júnior, 2019).

For Franciscato (2005), over the years, journalistic practice has adopted ways of observation and investigation based on science. "The use of photography, attention to spelling rules and clarity in the newsroom, the reporter's signature, the error correction policy, codes of ethics, among other elements, with the aim of becoming credible before the public" (Trasel et al., 2018, p. 7). Reginato (2016, p. 233) lists 12 functionalities of journalism, namely: “a) to inform in a qualified manner; b) to investigate; c) verify the veracity of the information; d) interpret and analyze reality; e) mediate between the facts and the reader; f) select what is relevant; g) to record history and build memory; h) to help understand the contemporary world; i) integrate and mobilize people; j) to defend the citizen; k) to monitor power and strengthen democracy; l) to clarify the citizen and present the plurality of society”.

It is evident that the objective of journalism is to inform clearly, with no room for guesswork. The veracity of the events has to be as close as possible and, as Charaudeau (2010) argues, the provision of elements to prove the facts, the evidence, cannot be considered a necessity, but rather an obligation of the journalist.

4. The impacts of fake news

In recent years, the whole world has been faced with a pandemic. We are not referring here to a problem that requires medicinal intervention, but to an embarrassment that urgently needs a solution that mitigates its negative impacts on society. We are talking about fake news, which is often disseminated in WhatsApp groups, Telegram, in posts shared on Facebook and Instagram, as well as in comments and shares on Twitter and TikTok, among other platforms.

It is important to note that fake news and information are not new practices, however, the strategy has gained strength recently with the overwhelming power of social media platforms, which reach millions of people in a matter of minutes or hours. The spread of news that misinforms gained evidence with the presidential elections in the United States in 2016 (Machado da Silva, 2019).

Wardle (2017) distinguishes some types of distortions that are disseminated on social media platforms. She lists seven categories of disinformation that were used in the 2016 U.S. elections, but which tell us a lot about cases in Brazil, such as the 2018 presidential elections:

“a) False connection: when the title or call does not confirm the content; b) False context: when genuine content is shared with false contextual information; c) Manipulated content: when true information is deliberately manipulated to deceive; d) Satire or parody: it has no motivation to cause harm, but can deceive readers; e) False content: misuse of information to frame a problem or a person; f) Impostor content: when credible sources are imitated by third parties; g) Fabricated content: when 100% of the information is produced to cheat or cause damage to something or someone”. (Wardle, 2017 as cited in Trasel et al., 2018, pp. 5-6).

The trick, at this juncture, involves the montage of photos, editing videos, distorting the contents of reports or bringing to light, with a totally out-of-context sense, old reports. The misinformation of the population in Brazil, and in the world, contributes to a chaotic scenario, in which people believe in pseudo-truths and share their opinion in a controversial way (Trasel et al., 2018).

In this context, it is worth mentioning that journalism is crucial to provide society with information for decision-making and positions in the face of events that require knowledge on the topic discussed. "Journalism is the business or practice of producing and disseminating information on contemporary issues of public importance and interest" (Schudson, 2003, p. 11).

In contrast to the large volume of disinformation circulating on the internet, Bill of Law 2630/2020 was created in Brazil, which establishes the Brazilian Law on Freedom, Responsibility and Transparency on the Internet, popularly known as the Fake News Bill. The Bill generated great repercussion in the media, with accusations against and in favor of the Law. Parliamentarians from the current government base argue that the initiative aims to combat fake news and punish those who share and create this type of content, in addition to providing obligations for search engines, digital platforms and messaging apps. The opposition, on the other hand, preaches that the approval of the Bill will generate censorship and curtail people's freedom of expression.

“Although the proposition of laws to combat the spread of fake news is frequent, the approval of these proposals proved to be a much more controversial challenge as they collided with economic interests, ideological polarization, or the disarticulation of political leaders”. (Vitorino & Renault, 2020 as cited in Paganotti, 2023, p. 214)

The fake news bill was approved on June 30, 2020 by senators, but is stalled in the Chamber of Deputies, amid a series of lobbies and pressure from big techs and various political and financial interests.

5. Methodological aspects and data collection

The present study refers to an exploratory and descriptive study. A work is considered exploratory when "[...] aims to provide greater familiarity with the problem, with a view to making it more explicit or to constructing hypotheses" (Gil, 2002, p. 41). The study is descriptive, as one of the objectives is to describe the particularities of specific audiences or occurrences. To this end, standardized techniques are used to obtain data, including a questionnaire (Gil, 2008). In addition, "studies of a descriptive nature propose to investigate 'what is', that is, to discover the characteristics of a phenomenon as such. In this sense, a specific situation, a group or an individual are considered as an object of study" (Richardson, 2012, p. 71).

We used the Google Forms tool as a research instrument. The choice was made due to the relevance and availability that the tool has, since it is completely free and online, facilitating and optimizing the collection of responses. In contemporary times, the use of printed questionnaires has made data collection difficult, as it requires greater engagement from the researcher and availability in the search for interviewees and their answers, not to mention that they would have to schedule a predetermined time for the approach. With the online form, these problems are overcome, since its scope is undoubtedly broader, without the need for scheduling, as everything can be done by sharing the link, and the target audience can respond when they have free time, not being limited to a certain time (Mota, 2019).

The form was divided into two stages. The first was to characterize the population studied, containing questions about age, gender identity, skin color, marital status, religion, and what period of the course the person is studying. "The information obtained through a questionnaire allows us to observe the characteristics of an individual or group" (Richardson, 2012, p. 188).

The second stage was specific, including objective questions, about impartiality in journalism, the sharing of fake news and disinformation on social media platforms, and also about the perspective of the journalism profession today.

In this way, with the online form produced, we sent it to the coordination of the Journalism course at UEPB- State University of Paraíba- so that it could be shared on the course wall on Google Classroom, being available to all journalism students at the university. We also sent the link to the form to the emails of the journalism professors for them to share with the students. The form was sent individually and directly, also, in WhatsApp groups and instagram direct to students of the Journalism course at UEPB, in addition to reinforcing the request in person in the classrooms. In general, the form was made available from October 30, 2023 to November 8, 2023, comprising a period of 10 consecutive days for collecting responses.

6. Characterization of the interviewed target audience

The study was aimed at students over 18 years of age in the Journalism course at UEPB. At the time of data collection, that is, in the 2023.2 academic period, according to information we requested from the course coordination, 469 (four hundred and sixty-nine) students were enrolled. Of this total, 62 actively participated in the study on a voluntary basis, which corresponds to 13.21% of the students enrolled in the university.

The study population self-declared as follows: 62.9% were female; 35.5%, male; and 1.6%, non-binary. Most are between 18 and 23 years old (58.1%), followed by those between 23 and 28 years old (25.7%), while about 9.7% answered that they are between 28 and 33 years old and, finally, 6.5% are between 33 and 38 years old.

Practically all students from all periods of the journalism course participated in the research, with the exception of the 11th. The highest number of responses was from students in the 8th period, followed by the 6th and 5th periods, both with 11, 10 and 7 responses (17.7%, 16.1% and 11.3%, respectively). Then, the 2nd and 7th periods appear, with 9.7% each, which corresponds to 6 answers in both. The 9th and 10th had a share of 8.1% each one. The 3rd and 4th obtained 6.5% each one. Finally, the 1st and 12th periods got only 2 answers each one, which represents 3.2% of the responding public.

Regarding skin color, 48.4% declared themselves white; 37.1%, brown; and 14.5%, black. With regard to religion, Catholic was the most declared, with 62.9%, followed by 24.2% who indicated that they had no religion and, finally, 12.9% reported being evangelicals. Also according to the answers, 93.5% of the interviewees are single, 4.8% married and only 1.6% did not want to answer.

After the first stage of the research, that is, the collection of the data characterizing the interviewees, we made available the specific questions of our study, which included several questions pertinent to journalistic work and the ethical implications of the profession.

7. Discussion of the data collected

7.1 Impartiality in journalism

We asked our interviewees, initially, if they consider that there is impartial journalism today. For this question we offer two answer options. The first was worded like this: "No, because from the beginning in the collection of information there are already choices based on the editorial line of the journalistic medium, on the directions of the agenda and on the profile of the journalist responsible for the content, among other aspects." The second: "Yes, because journalistic content goes through an objective process of information collection, investigation and textual construction. This process limits the journalist's inclinations from entering the material and makes it possible for the content to be unbiased."

Graph 01: impartiality in journalism

SOURCE: Prepared by the authors, 2024

The vast majority of respondents (82.3%, against 17.7%) answered the first option, considering that there is no impartiality in journalism today. According to Machado da Silva (2019, p. 37) "being impartial refers to not having a part, not having a prior side capable of conditioning the judgment. To take part without being a part, like a judge, who without being a part must take a stand and judge saying who is right." Now, it is true that this is the definition of impartiality in its purest synthesis, however, it is difficult for the journalist to exercise his profession without being crossed by factors that go beyond his decision. These factors are linked to the editorial line and the economic and political interests of the companies in which they work. In addition, there are aspects of the professional culture that also contribute to delimiting the relative autonomy of the journalist (Traquina, 2004).

7.2 Fake news, elections, and social media platforms

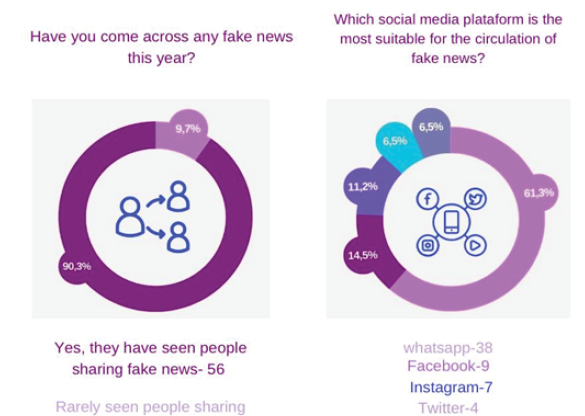

We asked our interviewees some questions about the circulation of fake news, especially during election periods, and whether they can contribute to changing the outcome of an electoral election. We also asked which platform was the most conducive to sharing/disseminating fake news.

For these questions, we considered the main social media and virtual message sharing platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter (currently X), Instagram, Tik-Tok, Telegram, Tread, and WhatsApp. Some of the options were not indicated by the interviewees, as shown in the following graph.

Graph 02: Circulation of fake news and social media platforms

SOURCE: Prepared by the authors, 2024

In general data, 90.3% of the surveyed public confirmed that they had come across some type of fake news in 2023, while only 9.7% said they had not seen, or rarely seen, fake news this year 2023. In another question, we asked which social media platform (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, Telegram, Treads, Tik-tok) was the most used for sharing fake news. Future journalists pointed out that WhatsApp (61.3%) was the most used, followed by Facebook (14.5%), Instagram (11.2%) and Twitter and Telegram, both with 6.5% each one. Tread and Tik-Tok did not receive any votes. Still on this topic, we wanted to know from the volunteers about the large circulation of fake news during the elections.

Graph 03: Sharing fake news and elections

SOURCE: Prepared by the authors, 2024

For 90.3%, fake news circulates more frequently in election years; On the other hand, 9.7% did not agree. At the same time, 96.8% stated that the large circulation of distorted/false news during the elections on social media platforms can change the outcome of the election; and only 3.2% reported that they did not, because people are more educated and can check the information.

These data presented notoriously illustrate the opinion of the students and affirm that fake news is a problem that deserves to be seen and fought, while underestimating its strength and degree of harm to the democratic process, not to mention the undeniable damage to the image of professional journalism.

In this context, the lack of a stricter policy that punishes those who create and share this type of content ends up giving people the feeling of comfort to continue practicing these actions.

7.3 Bill 2630/20, known as the Fake News Bill

Concern about the growing number of fake news sharing and the lack of stricter control by digital social media platform companies are the main reasons for there to be a movement in favor of Bill 2630/20, known as the Fake News Bill. The project aims to regularize the use of social media and seeks to prevent the spread of fake news, through robot accounts.

Approving a bill of law that intends to punish with greater vigor those who create and share fake news does not seem easy. The electoral justice in 2019, in fact, had approved an update of the electoral legislation and created a crime, called "slanderous denunciation for electoral purposes", the penalty was up to 8 years for those who committed the crime. However, the then president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, vetoed the provision. The veto did not follow, as the National Congress overturned Bolsonaro's decision and restored the provision (Valente, 2019). Regarding PL 2630/20, we asked our interviewees if they were in favor or against.

Graph 04: Approval of the Fake News Bill of Law

SOURCE: Prepared by the authors, 2024

The result points out that 62.9% of respondents are in favor of the project, while 4.8% said they are not, as it would generate some type of censorship, meanwhile, 32.3% answered that they do not know PL 2630/20.

7.4 Desires and challenges of the journalism profession today

The avalanche of fake news, misinformation, and attacks against press professionals are part of the daily life of the profession. Therefore, a credibility crisis has been installed, precisely in the activity that needs to convey confidence. We asked future journalists about the vision they have about being a journalist today.

Graph 05: Challenges and importance of journalism today

SOURCE: Prepared by the authors, 2024

For 45.2%, journalism plays an important role for society, providing people with information worked from specific techniques and knowledge, learned throughout the course and perfected in the daily practice of journalists and, therefore, remain confident in the profession. Another significant portion (33.8%) answered that every profession goes through troubled times and journalism would be no different.

However, more negatively, about 19.4% of respondents see the profession as demotivating and that it has been losing prestige and credibility in the eyes of public opinion. On the other hand, 1.6% consider it difficult to be a journalist nowadays, as there are countless fake news that professionals have to deny, among other reasons.

8. Final considerations

The role of the journalist has always been important for society. Plural journalism, based on facts, on everyday narratives, has always been and continues to be essential for decision-making. Bucci (2022, p. 6) cites that "[...] It is necessary to contest and correct disinformation. Yes, let's try to deny it. But if we want to overcome it, our biggest challenge as scholars is to explain it." Of course, the work of the journalist must be even more persistent, daily, but we still dare to say that this is a task of society, of everyone together.

The challenge for the journalist now is to make society understand that fake news and journalism do not fit in the same sentence. They accuse journalism of partiality; In fact, there is no impartial journalism, but there is also no journalism in favor of disinformation. Journalistic bias can be considered in terms of choosing an agenda or directing it, but professional and ethical journalism will not fabricate false information.

In our survey, according to data collected from the questionnaire, 82.3% of UEPB journalism students who responded to the survey, that is, 51 of the 62 students, agree that there is no such thing as impartial journalism. In the same questionnaire, 28 of the 62 students studied stated that journalism plays an important role for society, providing people with information worked from specific techniques and knowledge, learned throughout the course and perfected in the daily practice of journalists, and that for this reason they remain confident in the profession they have chosen.

Even though there is no total impartiality within journalism, as each one has its ideology, in addition to the company's editorial line, what should prevail are ethical and moral issues. Reporting what happened, transpiring and informing citizens will still be the most significant and valuable activities of journalism. It will be up to each of the users, the consumers of information, to navigate and get information from various press vehicles.

Our survey also revealed a reality that needs to be considered: 21% of students said that the profession of journalist is demotivating and difficult. This needs to be debated, after all, what will be the profile of these professionals when they enter the job market? What motivations will they have and how will each one's work be done? It is necessary for teachers and the students themselves to reflect on the subject so that this reality changes.

Thus, journalism has always resisted troubled periods, it has always been present and relevant. We hope that this moment will be just another one in which the profession will resist and continue to exercise its role of communicating and instructing people, providing them with knowledge so that they can make their own decisions and position themselves in the face of daily challenges.

References

Borelli, V. (2017). Midiatização, crise da enunciação jornalística e a multiplicidade de enunciadores. Alceu, 8(35), 35-46. https://doi.org/10.46391/ALCEU.v18.ed35.2017.117

Bucci, E. (2022). Ciências da Comunicação contra a desinformação. Comunicação & educação, n. 2, 05-19.

Trasel, M., Lisboa, S., & Reis, G. (2018). Indicadores de credibilidade no jornalismo: uma análise dos produtores de conteúdo político brasileiros. Anais do XXVII Encontro da Associação Nacional dos Programas de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação - Compós. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais.

Charaudeau, P. (2010). Discurso das Mídias. Contexto.

Costa, C. T. (2009). Ética, jornalismo e nova mídia:uma moral provisória. Jorge Zahar Ed.

D’Andréa, C. (2020). Pesquisando plataformas online: conceitos e métodos. EDUFBA.

Da Silva, L. J. C., & Júnior, A. E. V. P. (2019). Os saberes da pedagogia no telejornalismo: Paulo Freire e a prática jornalística. Revista FAMECOS, 26(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-3729.2019.1.31212

Franciscato, C. E. (2005). A fabricação do presente: como o jornalismo reformulou a experiência do tempo nas sociedades ocidentais. Editora UFS.

Gil, A. C. (2002) Metodologia da pesquisa. Atlas.

Gil, A. C. (2008) Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social. 6. ed. Editora Atlas SA.

Gomes, W. S., & Dourado, T. (2019) Fake news, um fenômeno de comunicação política entre jornalismo, política e democracia. Estudos em Jornalismo e Mídia, 16(2), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.5007/1984-6924.2019v16n2p33

Han, B. C. (2022). Infocracia: digitalização e a crise da democracia. Vozes.

Hepp, A. (2020). Deep Mediatization. Routledge.

Hjarvard, S. (2014). Midiatização: conceituando a mudança social e cultural. MATRIZes, 8(1), 21-44. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1982-8160.v8i1p21-44

Karam. F. (2004). A ética jornalística e o interesse público. Summus Editorial.

Lisboa, S. (2012). Jornalismo e a credibilidade percebida pelo leitor: independência, imparcialidade, objetividade, honestidade e coerência. [Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul].

Machado da Silva. J. (2019). Fake news, a novidade das velhas falsificações. In J. Figueira, J & S. Santos (Org.), As fake news e a nova ordem (des)informativa na era da pós-verdade (pp. 33-45). Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Manjoo, F. (2008). True enough. John Wiley & Sons.

Marcondes Filho, C. (2019). Fake news: o buraco é muito mais embaixo. In In J. Figueira & S. Santos (Org.), As fake news e a nova ordem (des)informativa na era da pós-verdade (pp. 17-31). Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Martino, L. S. (2019). Rumo a uma teoria da midiatização: exercício conceitual e metodológico de sistematização. Intexto, n. 45, 16-34. https://doi.org/10.19132/1807-858320190.16-34

Mintz, A. G. (2019). Midiatização e plataformização: aproximações. Novos Olhares, 8(2), 98-109. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2238-7714.no.2019.150347

Mota, J. S. (2019). Utilização do google forms na pesquisa acadêmica. Humanidades e Inovação, 6(12), 372-380. http://bit.ly/4aIomXU

Paganotti, I. (2023). Reações e impactos do “Projeto de Lei das Fake News” sobre o trabalho dos jornalistas. Eco-Pós, 26(01), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.29146/eco-ps.v26i01.28037

Reginato, G. D. (2016). As finalidades do jornalismo: o que dizem veículos, jornalistas e leitores. [Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul]. https://bit.ly/3EkC6fn

Richardson, R. J. (2012). Pesquisa social: métodos e técnicas. 3. ed. Atlas.

Schudson, M. (2003). The sociology of news. Norton & Company.

Souza Lima, L., & Oliveira Barbosa, S. (2023). 360° Audiovisual Journalism: a study on user perceptions of sense of presence and credibility. Brazilian Journalism Research, 19(2), e1553. https://doi.org/10.25200/BJR.v19n2.2023.1553

Traquina, N. (2004). Teorias do jornalismo. Por que as notícias são como são. Insular.

Valente, J. C. L. (2019). Regulando desinformação e fake news: um panorama internacional das respostas ao problema. Comunicação Pública, 14(27), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.4000/cp.5262

Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & Wall, M. (2018). The Platform Society: public values in a connective world. Oxford Press.